The Real Big Drip (RBD) is one of the most iconic climbs in the Canadian Rockies. With its high flow and susceptibility to chinooks it can be a bit temperamental. But when it’s in, it’s one of the best lines around.

The Real Small Drip (RSD) is a pair of seeps coming from the top of the cliff a few hundred meters to the left. You’d be forgiven for not noticing them as you stare up at the main attraction nearby. If you did notice them, you’d be unsurprised that no one had attempted to climb the steep face below to reach them.

In February of 2024, Raph Slawinski and I found ourselves staring up at the small drips after climbing RBD. It had been my first time on the route, and I was proud of my onsight of the first pitch. Raph was already a seasoned RBD veteran, having climbed it 25 years earlier. His may have been the second ascent, and possibly the first continuous free ascent. The details are lost to time.

There aren’t a lot of people that would look at 150 meters of steep rock guarding passage to a pitch of WI3 and think “That looks like a great mixed climb”, but I can say that there were two of them in the cirque that day.

Laying Siege

Any time you tie into a rope with someone, it’s a commitment and a partnership. A multipitch climb elevates this to another level. Attempting a first ascent takes it to yet further.

Committing to the siege of a wall adds a different element. With most climbs, you go out for a (possibly very long) day, and you go back home. Successful or not, the climb is over. Establishing a climb like The Real Small Drip is a long-term commitment. You’re making a plan to return to a place together again and again. We didn’t realize it when we started the project, but ultimately we’d spend about a week of our lives together on the route, spanning three winter seasons, before finally climbing the ice. I didn’t time it, but I suspect I’ve spent the better part of fifteen hours in various levels of discomfort at the belay below pitch 3.

Returning to a place together this often creates a sense of familiarity that borders on comfort. It’s a bit inhospitable, sure, but it’s a home away from home. Our gear is cached here. We have memories here. In the time we’ve been working the route, Raph went from having a foundation poured in Waiparus Village to living in a new home there. He can even see the top of the climb from just the right place in his neighborhood.

Early Days

Our early days on the route in the spring of 2024 produced varying amounts of progress. Our first day, I started with a run out lead, sparsely bolting a pitch that we’d later add a handful of additional protection bolts and fixed pins to.

Raph then worked up a steep corner and found his way to belay on a rail thin enough that you could only stand on it with your feet sideways.

One day, I forgot the drill batteries in the truck, and didn’t realize it until we were at our high point again. Raph assured me that he wasn’t upset, that he’d been climbing long enough to know that these sort of things inevitably happen sometimes. I believe his reassurances, but I still have a nagging sense of guilt about it to this day.

The day Raph bolted pitch 3 on lead was a bit of a revelation to me. I’d been establishing my own lines for a while at that point, but I did not realize how efficiently it could be done with good tactics and a bit of boldness. He bolted a pitch of M9 faster than I’ve worked my way through M6. He’d high-step off a bolt, and scratch around to find a single tooth tool placement to aid on. Fully committing to it, he’d drill another bolt, and the process would repeat. Writing about it now, it doesn’t sound crazy as it felt, but the vibe is very different when you’re dangling by the tip of your ice tool, with 70 meters of air beneath your feet.

Pitch four was my project. I adopted similar tactics, combining free-climbing sequences with aid. It isn’t as steep of a pitch as the third, but it’s steep enough to be almost as airy. I found myself leaning back on a tool hammered into a dirty crack, with a series of questionable cam placements beneath me. I trusted it too much, leaning outward instead of putting my weight downward into the aid ladder. The tool ripped out from the slot without warning, and my weight came onto the tether attached to my lower tool. That tool ripped out too and plummeted into the snow below, but not before snapping it’s pommel in half. Eventually the rope came tight on a .5 cam, which slid down the crack and became fixed. It’s still there today.

The 2024-2025 season was not kind to RSD. It never really came in. We did return to the route once, but only to work on pitch three. It just wasn’t motivating to try to push the line with no ice to work toward.

A diversion into ethics

Dry tooling and mixed climbing occupy a strange ethical niche when it comes to enhancing holds. In the rock climbing world it is essentially forbidden, but in frozen chossy slots there is a blurry line tapping your tool deeper and chipping a hold. A few taps will also seat your tool deeper into a shallow limestone edge. There’s something inevitable about it too, even without any intentional abuse, holds will naturally ‘beat in’ and become deeper (or break!) over time. No one really thinks twice about.

There are also places, including some dry tooling crags in the Rockies (and especially in Europe), where drilling pockets with a rotary hammer is completely acceptable and commonplace. When you’re just seeking to create a training venue for tools, this makes perfect sense. In a multipitch context, drilling holds trends more towards the gray, or possibly just black. For the same reasons it’s unacceptable in rock climbing, drilling holds on multipitch winter climbs in the Rockies is generally forbidden. There are a couple of notable exceptions, but even these are somewhat contentious.

Without fully litigating when it is and isn’t acceptable to drill holds, I’d like to make an important point that I don’t think many people fully appreciate the subtleties of. Enhancing a hold by beating it in with an ice tool is fundamentally different from using a rotary hammer, and even fundamentally different from using a carbide tipped bit and a wall hammer. It is simply impossible to create a useful hold in a blank face, or even a blank corner, with an ice tool. Trust me, I’ve tried. The best that you’re going to be able to do is strategically enhance an existing weakness. Your tool will naturally follow that weakness, and stop if it terminates. With carbide tipped bits, and especially with a rotary hammer, there is no such feedback. It will go wherever you point it, for however long you keep it running. And man is it easy to just squeeze that trigger for an extra second.

We agonized about this distinction establishing pitch three. One day was spent mostly bashing tiny holds into submission with a tool until they got to the point where they might plausibly hold up to repeated climbing. Dry tooling is a silly way to spend time in the first place, route development doubly so, but at the end of that day it felt slightly absurd that this was the way we were spending our free time. I come from a background of mechanically assisted crag-creation, but even the far more pure Raph was contemplating the idea of breaking our self imposed rule and busting out the drill. I thought that a hand drill with a ¼” bit might be a compromise, but I quickly realized that the ethical difference was not just manual vs. mechanised, it was steel versus carbide tips.

I do think there is a time and a place for drilled holds on a multi-pitch route, and I think Jimmy Skid Rig and Nophobia are reasonable instances of this. But now more than ever, I think that in our sacred places like the Stanley Headwall and the Trophy Wall, it’s better that a line not be climbed than that we start down the slippery slope of drilling holds. When the wall gets impossibly blank, a better compromise could be hooking a single bolt as a point of aid, a tactic which is already commonplace in the rock climbing world. I’m not saying we should never ever have a drilled multi pitch route, but it should be a vanishingly infrequent occurrence undertaken by only the most experienced and respected members of the community.

An end in sight

In the fall of 2025, pictures of RBD started appearing online with a thin-but-present RSD on the edge of the frame. It was time for Raph and I to return. We spent a session projecting the third pitch. I persuaded Raph that we should tick the tool placements with chalk to expedite the process, and he went along with it on the condition that we use white chalk, sport climbing style, none of that gaudy colored sidewalk stuff. We finished the session knowing that the pitch was possible, but it felt like far from a sure thing for either of us. Even if we were strong enough, a single unfocused moment could send us flying off of tenuous hooks.

Soon after, it was time for another crack at pitch 4. I’d spent a lot more time doing this sort of development in the intervening year and a half, but it still felt very real getting to and moving past the fixed (and now rusting) cam that I had whipped on previously. Again, a hybrid of free and aid movement led me upward. Slightly higher, I almost repeated my previous flight when a tool shifted out of its tenuous hook, but luckily it caught on a constriction lower down. Each time I gained a semi-reasonable stance to belay, a better looking option appeared above. I continued upward, eventually pulling onto a beautiful ledge and a perfect stance. It seemed almost unbelievable, but a sidewalk in the sky led directly from my stance sideways to the ice.

I was worried about the integrity of the ice, but when Raph came up he confidently took over to check it out. It was clear with his first tool swing that it would go. It wasn’t thick, but it was plastic and laminated. The route was climbable this season, as long as we got back to it and sent soon enough.

Send Day

A couple weeks later, send day arrived. Poor planning and excessive enthusiasm on my part meant that it was my third day on tools in a row, with the previous day being a somewhat tiring excursion on Drama Queen on the Stanley Headwall.

As in many aspects of climbing, Raph has quite stringent personal ethics on what counts as a free ascent. The lowest standard I’m willing to accept is that the FA party has freed all of the pitches on lead, even if they were sent on different days. A better standard is that all of the pitches are freed on lead, continuously by the party collectively in one push. The highest standard, which Raph tries to adhere to, is that at least one member of the FA party free all pitches in a push, and ideally both partners free them.

I loved the idea of both of us sending everything, but in my condition I was perfectly happy to support Raph sending the route, and leave my own completion for a later date. It was our third season working on it, and I’m just not that good at delayed gratification. Pitches one and two went smoothly. I could tell very shortly into pitch three that Raph was going to send. His movement was focused, calm, powerful, confident. Technical footwork in the overhanging crux led to a slip, and he swung around by his arms trying to free his ankle from the rope. But he quickly regained composure, and methodically finished it off. We’re not always overly emotive when climbing together, but that moment had us both cheering, our voices echoing around the amphitheater.

It was my turn. I was exhausted from the previous days, and had figured I would just hang-dog and measure some draws for later replacement with fixed chains. But Raph’s movement inspired me. I had to at least give it a try while seconding. I let go of our haul bag, which swung 10 meters out into space behind me, and realised I hadn’t put my puffy pants in it. Screw it, I’m cold, I’ll climb in them. The climbing went well at first. My body was tired but my mind was focused, and I was able to breath and keep a gentle grip on my tools. When I got to the crux sequence that had sent Raph swinging, I could not find a place to keep my feet on. Instead, I fully inverted, plastering my heels on the wall beside my tool, wearing puffy pants. I spent half a breath appreciating the absurdity of the situation before realizing that I might actually pull off a top-rope send, and I kept cranking. Many tenuous moves later I found myself approaching the belay, with my face beside Raph’s crampon. I skipped a hold obscured by his knee, and then blew the final tool placement, sliding down the slab, shredding the knees of my pants, and not technically freeing the pitch. Oh well, it’s an asterisk on top of the existing asterisk of it being a top-rope send. I’ll be back to climb the pitch cleanly, but if I can send it in puffy pants after a Headwall day, I’m sure I can send it when I’m fresh.

Push it across the line

Pitch four loomed above us. After an awkward transition, I took off with the trad rack. For the first two bolts, you’re at risk of landing back on your belayer, and I was only barely past them when I popped off. I sat on the rope and hunted around for a better hold before lowering back to the belay and trying again. The crux of the pitch is about 10 meters in. It’s a huge stein pull, and you need to engage it, work your feet high up on a hanging slab, and lock off deeply before a series of tenuous hooks lets you pull around into a deep corner. My heart wasn’t in it. The previous pitch, and the previous days of climbing, had pulled all the inspiration out of me. I just wanted to go home. But even more than that, I wanted to complete my redemption by actually sending the pitch for the first time, and I forced myself to push through.

There is gear to be found once you gain the corner, but better yet, there is a proper no hands rest once you go higher. The allure of the shake outweighed the allure of protection. Worst case scenario, I would go for a long ride into the vast space beneath the overhanging wall. I made it to the rest, shook, got some gear, and then slowly worked upward, one questionable placement at a time. Eventually I started to properly enjoy myself again, and by the time I was at the belay, my despair gave way to euphoria.

Raph followed, then grabbed the ice screws and ventured into the unknown. He cruised up thin ice protected by sporadic stubby screws. Eventually he went out of sight and I heard the sound of a piton singing in. I kept paying out rope, and we tried to shout back and forth about the meter of it that was left. A quick phone call let Raph know he was out of rope, and let me know he was at the top! He hammer in a piton anchor and I seconded with the drill.

The pitch was delightful. He’d previously named a route “The chase is better than the catch”, but this was the opposite. Thin ice gave way to the best flavor of mixed, where you have one tool and one crampon on rock, and the others on ice. I cleaned sporadic cams before arriving at a triple piton belay.

It’s not over until it’s over

We’d finally finished it. I blasted in ring bolts, and we began our descent. The first rappel went smoothly enough. Then I rappelled from the top of pitch four to the middle of pitch three, and established a new anchor. My hope was that we should be able to reach the ground from there, without the pain of fully reversing pitch three. Raph joined me, and pulled enough of our ropes through that we didn’t have a handle on the tail anymore. Then, they got stuck. Ten minutes of thrashing ensued. We both conceded to the idea of leaving it and trying to descend using a 30 meter length of tag line that we had in the haul bag. Raph asked if I had any last suggestions, and I offhandedly remarked that we could try springing the rope free by pulling forcefully down and letting go suddenly. It’s not something that’s ever worked for me before, but hey, why not. I wasn’t even watching, when Raph tried it, and an incomprehensible sound of elation came from his mouth. Magically, the rope was moving again.

There are moments in our lives that will stick in our memories forever, and occasionally, you know it while you’re in them. I did a slow 60 meter fully free hanging rappel down toward the ground. A full moon shone into the cirque while thin clouds slid by. The Real Big Drip glowed in the moonlight beside me, its steady flow sounding like a peaceful fountain. The serene, snow covered Ghost River Wilderness extended out of the valley before me. The beam of Raph’s headlamp danced around far below. I savored the moment as I slowly spun in space.

The Real Small Drip

Ghost River Wilderness

M9+ WI3+ 185m

Greg Barrett, Raphael Slawinski

Dec 4, 2025

This is a very wild line that is likely to have niche appeal. If you enjoy both scrappy heads-up trad and overhanging technical climbing on bolts, then it’s a great adventure. It can also be a good fall-back if you reach the base of The Real Big Drip and find it out of condition.

This route was established over the course of three climbing seasons. The FA party returned many times, racking up from a cache each time and re-climbing the lower pitches before getting to work. A great deal of time was spent finding workable sequences through the many roofs on pitch three. Holds were beaten in with an ice tool where they were too thin to be usable. Ethically, they find this to be fundamentally different from using carbide tips and rotary hammers. When holds inevitably break on this route in the future, they implore you to adhere to this ethic when fixing them.

Approach

As for The Real Big Drip. The route starts a couple hundred meters lookers-left, in a chossy right facing corner. Two bolts are readily visible from the ground.

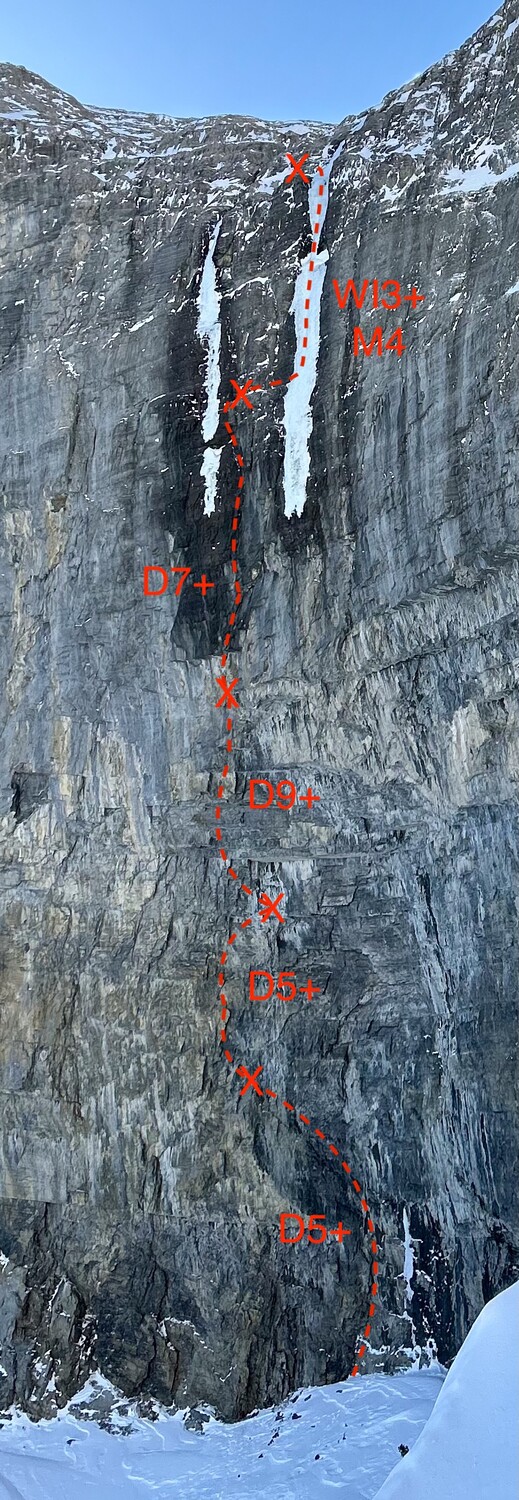

P1, D5+, 30m

Climb the loose corner on a mix of gear and bolts. Tenuous climbing leads up and left to gain a left trending ramp. Follow the ramp past fixed pins and bolts to a pedestal belay. Trad gear is only required for the first corner.

P2, D5+, 25m

Climb tenuously up and left to gain a steep right facing corner. Follow this corner, eventually pulling out left to surmount it. Continue upward on easier ground until you reach a hand rail leading right. Traverse this rail and mantle up to a belay below a large white roof. For this pitch, you need gear for the crack visible from the belay, plus a selection of finger sized pieces above.

P3, D9+, 25m

Climb the steep right facing corner to a roof before breaking out left. Follow bolts through a series of roofs before finding a shake in a large right facing corner below yet another roof. At this point, step right across the slab (passing a rappel station), and continue up a steep wall before escaping left beneath another roof. Thin climbing leads to the belay. This pitch is fully bolted past the first roof. You only need trad gear for the cracks you can see from the belay. This pitch was ticked with white chalk during the FA, feel free to do the same if you’re projecting it.

P4, D7+, 45m

Climb the shallow groove above the belay past two bolts. Trend rightward on progressively more exposed ground. A burly crux guards access to a deeper right facing corner and a shake. Climb the corner to its top, and lean out to clip a bolt around the face. Continue up a steep groove past a fixed cam, trending left. Eventually, arrive at a large sloping ledge in a large left facing corner. Climb the corner and exit right onto a giant belay ledge. Bring the whole rack for this one.

P5, WI3+ M4, 60m

From here, either of the two drips can be accessed.

If the left drip is formed, climb a short distance left to gain it, following it up through a choke to a large ledge system. Find a bolted anchor to the right, halfway along the ledge.

The FA party climbed the right drip, which can be gained by traversing 5m rightward from the belay. The character of this pitch will vary widely depending on conditions. For the FA party, it involved 20m of thin ice on stubbies before the ice ribbon narrowed. The remainder of the pitch was proper mixed climbing with rock protection. Continue to the same anchor located on a ledge running between the drips.

Descent

From Pitch 5

- 60 meter rappel straight down to P4.

From Pitch 4

- 45 meter rappel down to the P3 anchor, clipping back into the first four bolts of the pitch when you get to them. A cam in the #1-3 range will help you get back to the third bolt.

From Pitch 3

- 70m ropes may reach the ground, but be very sure of it before committing.

- If not, rappel approximately 10m to the fully hanging station halfway through P3. A 60m rappel reaches the ground from here.

- Alternatively, if you fix a rope between the P2 and P3 anchors on the way up, you can rappel between those two stances without back clipping in.

From Pitch 2

- 60 meter rappel straight down to P4.

Gear

A minimal rack would consist of .3-4, doubles .3-3, and a handful of short screws. A party wanting more protection could add small to medium nuts, some blades and peckers, and a larger selection of screws in fat ice conditions.

A bosun chair or butt bag is also advisable. The belay at the top of P3 is fairly unpleasant otherwise.